17 January 2023

|

From Georgemas in the north, via Peterhead in the east and Whithorn in the south, to Mallaig in the west, if you’re looking for Scottish railway ancestors, the Railway Work, Life & Death project might be able to help you!

The Railway Work, Life & Death project is looking at accidents to railway staff in Britain and Ireland before 1939. Our free database of staff accidents details what happened, to whom, where, when and why. It tells you about the people involved and what their day-to-day jobs entailed. With nearly 4,000 Scottish cases in the database already – and more to come – there’s lots to explore.

What if your railway ancestor didn’t have an accident? Well, the project still has plenty to offer. Sometimes there’s an accident in the database that wasn’t known about by descendants. And even if your ancestor didn’t have an accident, there’s a good chance that people in the same role did, so by looking at their details you can get a much stronger sense of what your ancestor did as part of their job.

At the moment the Railway Work, Life & Death project’s coverage starts in 1900 and ends in 1939. We’re extending that back into the 19th century as we bring more records into the project. Through the project records, we can learn more about the people keeping Scotland’s railways moving.

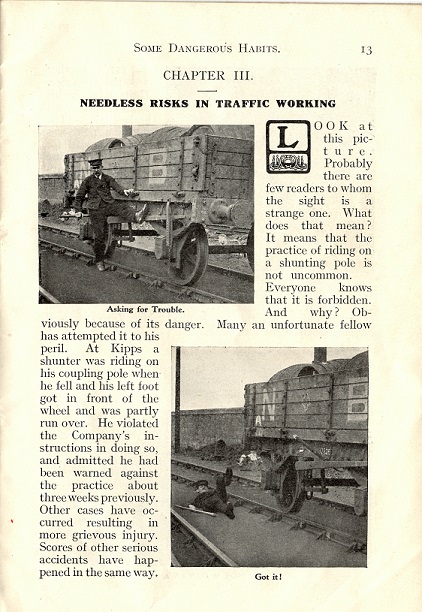

Cover of North British Railway staff safety booklet, c.1914

That includes, for example, the circumstances behind the death of fireman J Murray in Motherwell, on 11 December 1939. He was oiling his engine, preparing it for service, when another engine made contact with it. Murray was crushed by the motion, and died six days later. The entry shows that low lighting – because of the Second World War – was partly responsible, and that the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company was to look at improving the lighting, having already blacked out the engine shed roof and windows.

Exploring social and political issues

Via cases like Murray’s we can see the impact of much wider social and political issues on people’s everyday lives – whilst of course the database focus is on the railway industry, it is also full of details of social history. For example, we see the ways in which women were employed in the railway industry. Often this was in roles that many in the era felt ‘appropriate’ for women – as carriage cleaners or gate-keepers at level crossings. Sometimes, though, we see less typical roles – like that of Janet Hewitt, part of a gang of women and men unloading pit props at Kinneil when she was injured in 1923 (read more here).

We also get a sense of the incredible range of ages of people working on and around Scottish railways. At the lower end of the spectrum our database features 12 to 14-year olds, like John Watt, who lost a foot at Townhill Junction in Fife in 1930, when he was reading wagon labels (to record them) and an engine ran over his foot. At the upper end of the spectrum, we have 11 workers in their 70s, including Charles Spence, 76, who was knocked down by a train in 1908 in the course of his job at Airdrie. The report noted that despite his age ‘he was considered a smart active man capable of carrying out his duties.’

Page from the North British Railway staff safety booklet, warning of one danger incurred by some goods staff

The records currently in the database are transcriptions and summaries of accident investigation reports carried out by inspectors appointed by the state. Teams of volunteers at the institutions collaborating on the Railway Work, Life & Death project – the University of Portsmouth, the National Railway Museum and the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick – have spent thousands of hours making these records available to you. We’re enormously grateful for all of their hard work!

There’s an enormous variety in the database, giving us all a much better impression of how complex – and how dangerous – the railways were before 1939. Whether your ancestor worked in a role you might have heard of - like driver, station master or porter – or one you haven’t heard of or didn’t expect on the railways – like ‘brasser,’ diver, bottle boy, ‘wedger’, or ‘red cap’ – you’ll find them in the Railway Work, Life & Death database.

Page from a 1930s staff safety booklet, warning of the dangers of crossing railway lines in crowded railway yards

It’s also worth saying that it’s not just railway workers you’ll find in the database. Plenty of people had reason to be about railway property, and ended up finding themselves in harm’s way – merchants collecting goods, carters, contractors, farm employees, stevedores and more. Over 200 people feature in the database in this way, including 82-year old John McNaughton, injured in Stirling in 1928. He was riding in the brake van containing the sheep he was delivering, when it collided with other vans; McNaughton fell to the floor, suffering cuts and bruises.

In addition to the free project database, our website tries to tell the story of the accidents and the people involved, including their families. There’s a weekly blog, looking at one or more of the cases (choose from the Scottish cases here), and other resources to help you understand more about the dangers of working on the railways in the past.

How to get involved

Family historians are a crucial part of the project, too. We’re collaborative in our approach, and the expertise that family historians have generously offered, in a variety of ways, has helped us better understand the people involved in railway worker accidents and the impacts the accidents had, including on the wider family. Our thanks, therefore, to you all, too, for getting involved and sharing your insight.

In particular we welcome guest blog posts, giving the family’s perspective on railway staff accidents in their family’s past. This might be for individuals found in the project database, but it might go beyond that (as sadly plenty more people had accidents on the railway than were investigated at the time). Some examples of guest contributions are found here; if you’re inspired to ‘write up’ the railway accident in your family past, please read our advice here and get in touch!

It’s also worth keeping an eye on the project – with our lovely volunteers, we’re working on many more records to add to the database. The next update, scheduled for this spring, will bring around 25,000 trade union records into the project, significantly extending our coverage, including back into the 1880s.

If you use the database or any of the other project resources, all available free from the project website, and find someone you’re researching, please let us know – we’d love to hear about it and how it’s helped you! We pass this on to the project volunteers, too, as it gives us all a boost to know what we’re doing is being used and appreciated.

Follow the project on Twitter (@RWLDproject) or Facebook for more. Find all our resources, free, on our website.

Dr Mike Esbester, one of the project co-leads, is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Portsmouth, where he researches and teaches on a variety of topics, including the history of safety, risk and accident prevention in modern Britain.